THE TIMELESS LAND- WHY I KEEP GOING (HOME) TO CORNWALL

‘It must indeed be a strange land that has laid its mysterious touch upon so many people, such a variety of Artists. What has made Cornwall such a strange world? Why has it drawn so many creative artists? In which manner has it inspired and influenced their work? Is the veil indeed worn so thin in the Kingdom of Kernow that by living and working there creative artists are nearer to occult powers that (perhaps even without their knowledge) provide some extra stimulation? Just what does it all mean and reflect, this strange, perhaps unique interweaving of artist and atmosphere, of landscape and work, of sea and granite, image and epithet?’

Denys Val Baker, The Timeless Land- The Creative Spirit in Cornwall, 1973

Anyone watching my Instagram feed over the last few weeks will know that I’ve been away again, to Cornwall, a place that feels like home to me, even though it isn’t… yet… And those of you who have asked me how I enjoyed my time away may well see me breathe in deep, smile, and glaze over with that far away look, as if trying to recreate that nameless, infinite feeling of being back in my favourite place in the world.

Yes, it’s a beautiful land, its appeal influenced by its location and geography, a peninsula jutting into the Atlantic, out on a limb, the most westerly of all English counties, and that with the highest mileage of coastline. Cornwall is favoured by warm winds and a balmy climate (except when it’s not!) and one that has attracted artists for many decades.

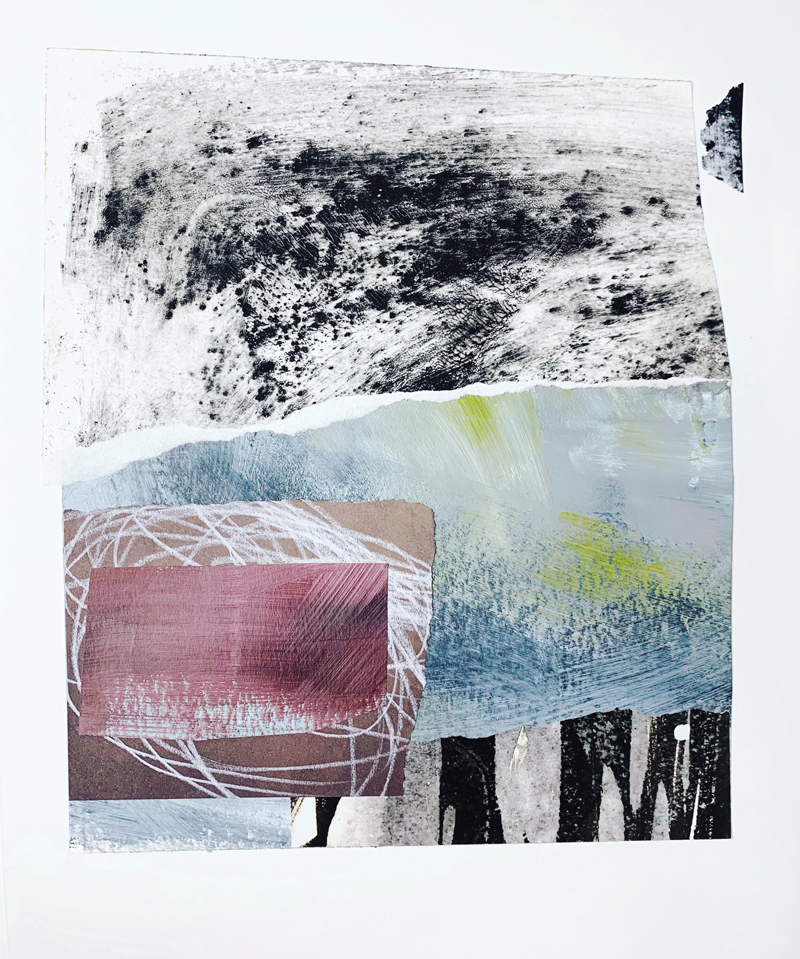

I’ve been reading and walking and painting my way into the landscape for years, fascinated by a terrain that holds so many secrets, and pondering over what lies beneath this in-your-face topography that makes me want to learn more about the making of the granite and greenstone landscape.

I’m absorbed by the wiry grasses growing between sharp, dark rocks; the ancient and abstract gorse clad field boundaries with the Cornish hedges hosting the most uplifting array of flora; the deep zawns (clefts in the rocky cliffs) that gape below me, the waves churning and tumbling with an energy that takes my breath away. I feel an urge to express the sense of being in this place; the heady smell of gorse, salt spray and seaweed; the feeling of leaning into the wind on a high tor; the sounds of choughs in the undergrowth and pebbles washing against the shore. The work is this; to absorb these stimuli and create work that illustrates this in an emotive and meaningful way.

Artists are known too for being drawn to the light, especially around St Ives. Certainly, there is something about the light- a crystal clarity on clear days, a diffuse shimmering even on grey days. But it’s more than the physical beauty, and this is where it gets hard to explain. How does landscape affect us if not purely in a visual sense?

I am so interested in exploring the unseen or sensed ways in which landscape affects us. Everyone responds to the landscape in different ways. If I’m walking alone I’ll gravitate towards the forest- with a friend we’ll choose more open spaces. I’m more of a moorland and hilltop person than a beach person- though I love exploring the rocky hinterlands of Cornwall’s sandy beaches. Cities make me feel on edge and exhausted, and although in the short term I enjoy all they have to offer, it’s the natural landscape that allows me to feel massive ‘Positive Affect’- feelings of awe, elation, and affection as well as an increase in my productivity and creativity. (Studies have shown that blood pressure and heart rate are decreased with exposure to nature. )

A couple of weeks ago I took my own pilgrimage from Lelant to Marazion, on St Michaels Way, across the Penwith peninsula that traders and pilgrims have followed since the Bronze Age. Sitting in a sun-warmed spoon of rock on Trencom Hill I could see the north coast from where I’d started across to the south and St Michael’s Mount, my destination.

Heady with halfway fatigue and low blood sugar I could, I am convinced, feel the energy vibrating through the land from Ireland and Wales to Brittany and beyond. I did feel like a pilgrim seeking and spurred on by an unseen force, conscious of the footsteps of all those who’d gone before.

In West Cornwall, in layers amongst the geology- the igneous outcrops and rocky tors- lie countless granite monuments – quoits, cairns, standing stones, crosses and cromlechs are all evidence of a real and spiritual past, hints of civilisations that understood things in ways we can only guess. And it’s here, where ‘the air is thin’, that I sense another power, another dimension which makes my spirits soar.

Cornwall manages to blend myth and reality in an intoxicating mix. Old Stories exist of the Cornish giants of Trencom and St Michaels Mount tossing rocks to each other across the fields. There’s plenty of physical evidence to support this in the fields of boulders that lie beneath.

I don’t know what attracted my maternal grandfather here before the war and raise his family but maybe he sensed the same as the generations after him- a keen sailor, the tidal creeks of the south coast attracted him and as they did my own parents when they decided to move back the very day I left for University in 1986!

When I visit now I go to escape the noise and overstimulation of everyday life ‘upcountry’. It’s geographical and cultural distance from the rest of the country reflects the sense I often get of an apartness -from the world, from politics and parties and people.

It’s sometimes savage, often benign beauty is stimulating in the extreme, and yet calming too. In Cornwall, I feel grounded, and certain, as if I’m enveloped in an aura of positivity. I know I’m only a visitor, and possibly will only ever be a transient citizen, but to my heart it is home, so my friends can expect me to muse wistfully over my spiritual homeland for a long while yet!